|

page 52 ART of the WEST . January/February 2008

When Work is Done, oil 48" by 42"

‘Set in the late 1830’s, two fort employees take a break from work. A perennial favorite board game, checkers originated in Africa over 4000 years ago. It was played in various forms by the ancient Egyptians. Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and later, throughout the modern world. The fellow on the left holds a buffalo tail fly-whisk and the other fellow sits on a slanted hide-fleshing log … which is why the first guy needs the fly-whisk.”

MEMORY KEEPER

By Mary Nelson

A couple hundred years ago, before information swirled around the world in books, newspapers, television, and on the Internet. artists were historians. Bards and poets kept history alive through verse, dancers pantomimed the significant and banal events of the day, and painters sketched visual

references lest mankind forget the people and events that came before.

Joseph Velazquez is a modern-day equivalent of those ancient memory keepers who traveled from town to town singing, dancing, and painting the human experience. An avid historian of the fur-trade era, he lifts the words from the journals of pioneers, trappers, and the women who traveled the Oregon Trail and gives us an image of a life we cannot comprehend.

‘Trappers were, by and large, very literate,” Velazquez says. ‘[They] loved to read and treasured hooks. So many of them left journals and, when you read those journals, you are right there. That’s not a screenplay. It’s the real thing and reading them puts you there. I’m amazed bow tough these people had it, how they persevered, and they went through unbelievable hardships.”

Velazquez, eloquent in recalling his own history, immediately lets you know that persistence is how he got to where it is today. During World War LI. when his Father was serving his country his mother helped to secure her son’s destiny by bringing art supplies home from shopping trips as a treat, in part to keep his attention from the absence of his father. High school pals kept the spark alive by asking him to draw pictures of family members, sweethearts, and movie stars. Velazquez just never thought fine art could be a career.

“I don’t think most people, collectors, really understand the commitment it lakes to make it in this business,’ he says speaking not only of himself but of all artists. Velazquez credits his success to persistence and goes on to quote Calvin Coolidge: “Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.’

During college, Velazquez earned money by creating architectural delineations for local builders. He. left Colorado State University in 1963, before earning a degree, because he was eager to start a career. At that time, illustration jobs in Denver were few and far between, so he worked in commercial art studios, doing production, layout, and design. In 1970, Velazquez started his own advertising agency—Velazquez, Goddard and Maul—which lasted for five years.

In 1975, Velazquez took the plunge into fine art. By that time, he and his wife Pam had set up housekeeping

page 54 ART of the WEST . January/February 2008

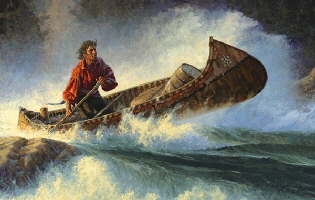

Threading the Needle, oil, 42” by 48”

“A free trapper (one that didn’t work for the HBC or Northwest Company) navigates his canoe through some serious rapids. He has been through here many times before and knows exactly where he can make it through and avoid an arduous portage. The canoe is a light canoe of the Ojibwe long-nose style. I utilized color temperature differences and heavy contrast to enhance the drama and action.”

Ojibwe Dawn. Oil, 24" by 72"

“An Ojibwe Indian holds his bow and several birding arrows. This type of arrow did not have a sharp bone or metal point, but rather a blunt point for maximum impact. For rapid shooting, several arrows are at ready in his bow hand. A good archer could deliver six to eight arrows in the air before the first hit the ground. The canoe is the Ojibwe long-nose style. The decorative design on the side is a strip of reinforcing bark which helped prevent the lashings from tearing through.”

Ojibwe Night, oil 30” by 48”

“When I planned this painting I felt the feeling of night would be enhanced if the water was virtually black except for the reflections. The fignres and objects proved difficult to paint because the range of values was exceedingly narrow. The challenge really ran me ragged.”

- page 55 January/February 2008 ART of the WEST

- Running the Chute, oil, 36 by 72

- “Two free trappers take on the rapids. It is a lot of fun to paint these action scenes set on turbulent rivers.”

in Centennial, Colorado, once rural but now part of Denver. Pam, an artist herself, understood her husband’s need to delve into fine art, and together they decided he should take the leap.

‘She’s been so supportive of me,” Velazquez says of Pam. “This hasn’t been an easy life. When I first made the transition into fine art, one of the requirements was I couldn’t step down. I had four children, a wife, and a mortgage. I couldn’t say, ‘Let’s go live in a tent while I pursue my dream,’ But she went along with that and stood by me.

Velazquez did his first sculpture in 1979. “1 thought there had to be a steep learning curve [with sculpture], so I went to some sculptors and asked what I needed to know,” he says. ‘They said, ‘Well just sculpt it and, if it stands up, the foundry can cast it,’ That was about it,” Velazquez laughs as he recalls that advice and then admits that he gives the same advice, because it’s essentially the truth. Even though sculpture was gratifying and an interesting form of expression, the demands on time that sculpture requires forced Velazquez to choose between painting and sculpting; painting won.

“I have so many ideas that I’d never accomplish them in three lifetimes,’ Velazquez says, adding that years ago he’d get an idea for a painting, literally, one at a time. I’d get an idea, do the painting and that was that,” he says. Today he might have as many as 15 or 20 ideas percolating, sketched on pieces of paper, sometimes as small as 3” by 5”. Each one is plotted and planned until at last, when he chooses an idea, the initial concept has become a full-blown picture in his mind.

“I used to draw a lot with charcoal,’ Velazquez says. ‘I don’t do that now. I pretty much draw with a brush. The time [I spend] in planning a painting has served me well. I used to paint myself into a corner by not planning well enough in advance. Now I start with a wash drawing and draw the main elements. Then I delineate the figures and block out the values and it all falls in place.

When working with a wash drawing, Velazquez explains, it’s easy to add color or remove it. ‘So, between using a brush to add the wash and a Q-tip to remove it, I can establish the look of that figure or that canoe, the basic composition” he says.

Velazquez says he doesn’t put a label on his style, preferring to leave that to others. His artistic tech-

nique, however, he will discuss at length. For about three years early in his career, Velazquez worked with acrylics, but he was bothered by the hardness around the edges of the medium, so he turned to oils, hoping to achieve a softer, more pleasing effect. The transition was difficult, but again, he persevered. In doing so, he has developed a two-stage method of painting that serves him well.

Once he has drawn the main elements on the canvas and is comfortable with the proportions, Velazquez lays down the basic paint, lets it dry, and then goes into most everything again. “[Let’s say] I’m doing a sky,” he says. “If I lay in a sky, I have these different colors. If you mix certain colors, you will get a color you don’t want. You may have a sky with blue hues and some warm hues with yellow but, if you put blue and yellow together, you get green. In order to combat that, you lay in the cool colors and you go back in with the broken color technique and lay in your warms and let them play against one another.”

Using this technique, Velazquez infuses the colors with a light that makes them glow, gives them life. In essence, he steeps his paintings with the emotion he gleaned from reading the journals and history books of

- page 56 ART of the WEST . January/February 2008

- the fur-trade period. “I want people to he moved emotionally by what they see; the beauty of it, the drama of it” he says. “It has to be attractive but I want them to feel the passion of what [I put] into the people or the scene that they are viewing.”

There had never been a doubt in Velazquez’s mind that he would be an artist. Although he didn’t set out to herald the fur-trade period, he took an interest in the people and their lives after he read The Big Sky” by A. B. Guthrie Jr. for a college literature class. He was so taken with the period, landscape, and people that he molded them into his subject matter, using his paintings as a reminder of a fragility of the world and its people.

Although Velazquez concedes that his work as an illustrator was art, it didn’t give him the opportunity to experiment or explore that his fine-art career has provided. While he didn’t lack for idols or artists who piqued his creativity, Velazquez always wanted to he his own artist. “I think all artists, when they first start, are enamored with one artist or another,” he says. “I thought Frederic Remington was wonderful. I loved the way Remington handled paint. It behooves an artist to move beyond that as quickly as possible, though. I can look and observe and say. That’s wonderful,’ but the last thing I want to do is paint like somebody else.”

Nor does Velazquez ever want to stop exercising his artistic talent. He expects always to improve, to make each painting better than the last. “I push myself to experiment with a lot of ideas that would he kind of dicey some that may work and may not,” he says. “Usually I’m happy enough with [an experiment] to say, ‘Yes, I’ll put my name on it.”

In the end, Velazquez’s objective for his art, he says, ‘is to be a reminder of the fragility of the world and its people we treasure. When a painting is complete, I judge its success by the emotion it evokes from the viewer.” (AW)

- page 57 January/February 2008 ART of the WEST

- Morning Rain, oil, 36” by 60”

“In this painting the weather provides the key element. The wet ground and the early morning light set the mood. The wet barn roof made of CCI or corrugated galvanized iron, reflects the light of the sky. CCI was invented in Britain in 1828 and was rapidly adopted as an inexpensive and practical building material throughout England. the United States, Australia and later India. Thousands of structures were built or roofed with CCI during and after the California gold rush of 1849.”’

Mary Nelson is a writer living in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Return to

About Joe

|